It is said that adverse conditions make for hardy people. Living in Montreal Canada is no exception. Today’s guest JOSE HOLDER is both a multi-talented individual and a positive force to be reckoned with…and we’re glad to have made his acquaintance.

BTP: Tell us a little bit about yourself and why you decided to pursue your career as a creative storyteller.

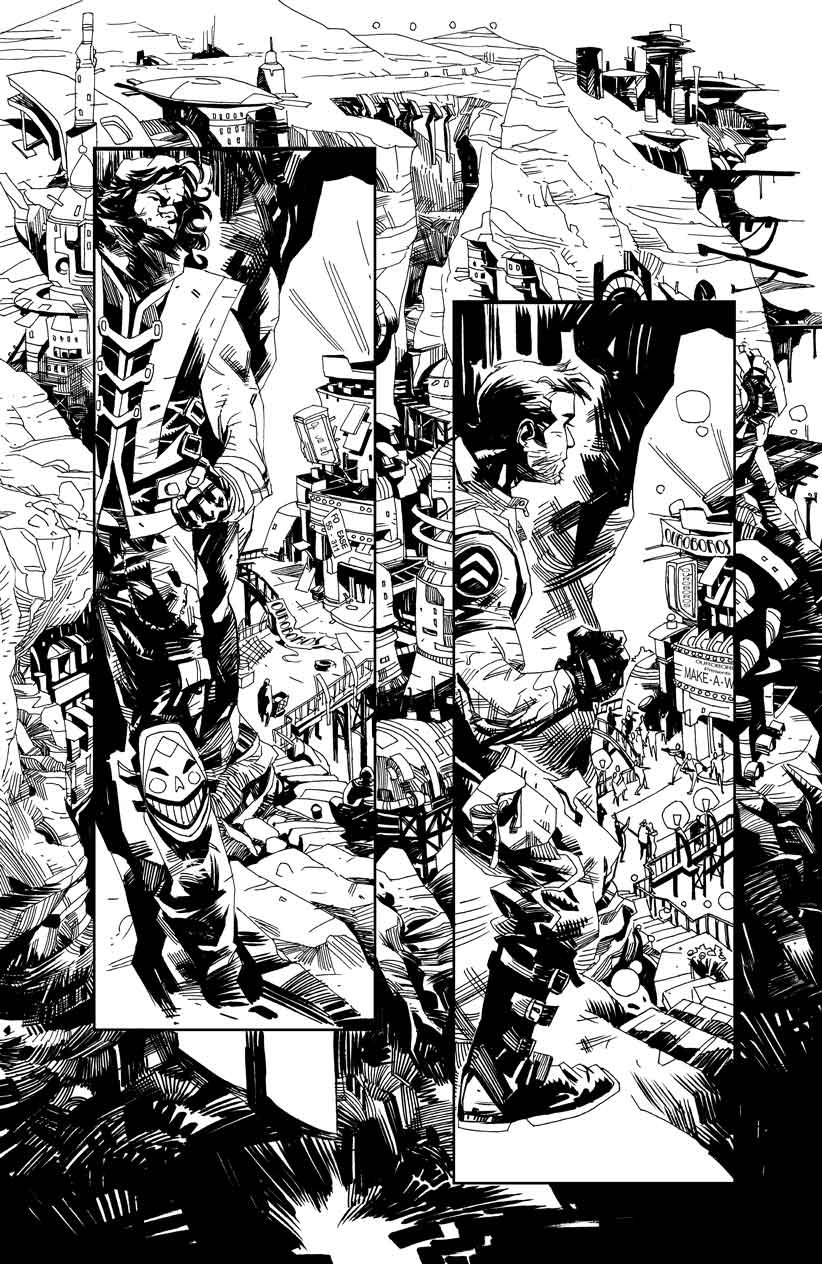

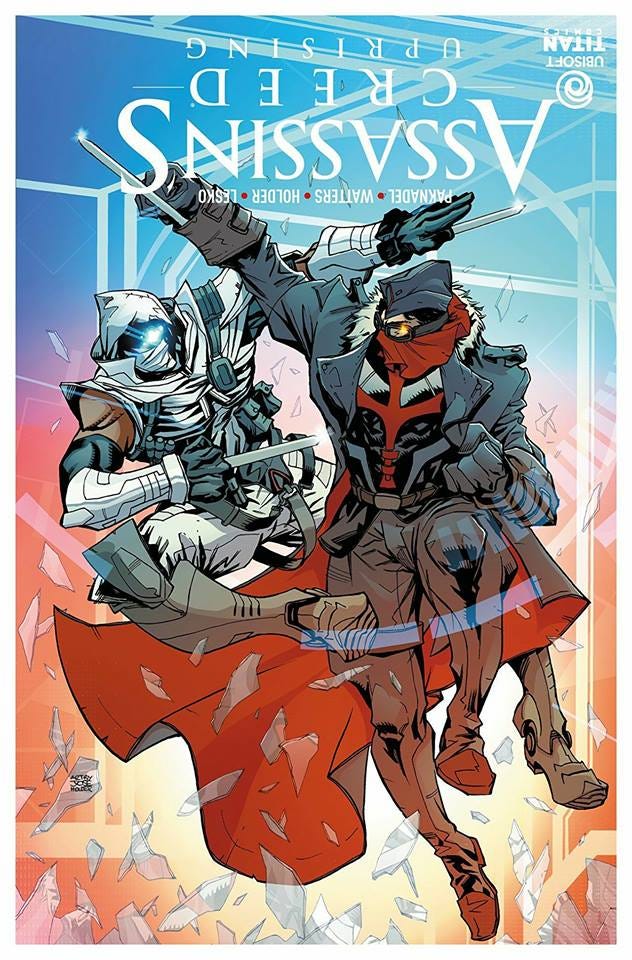

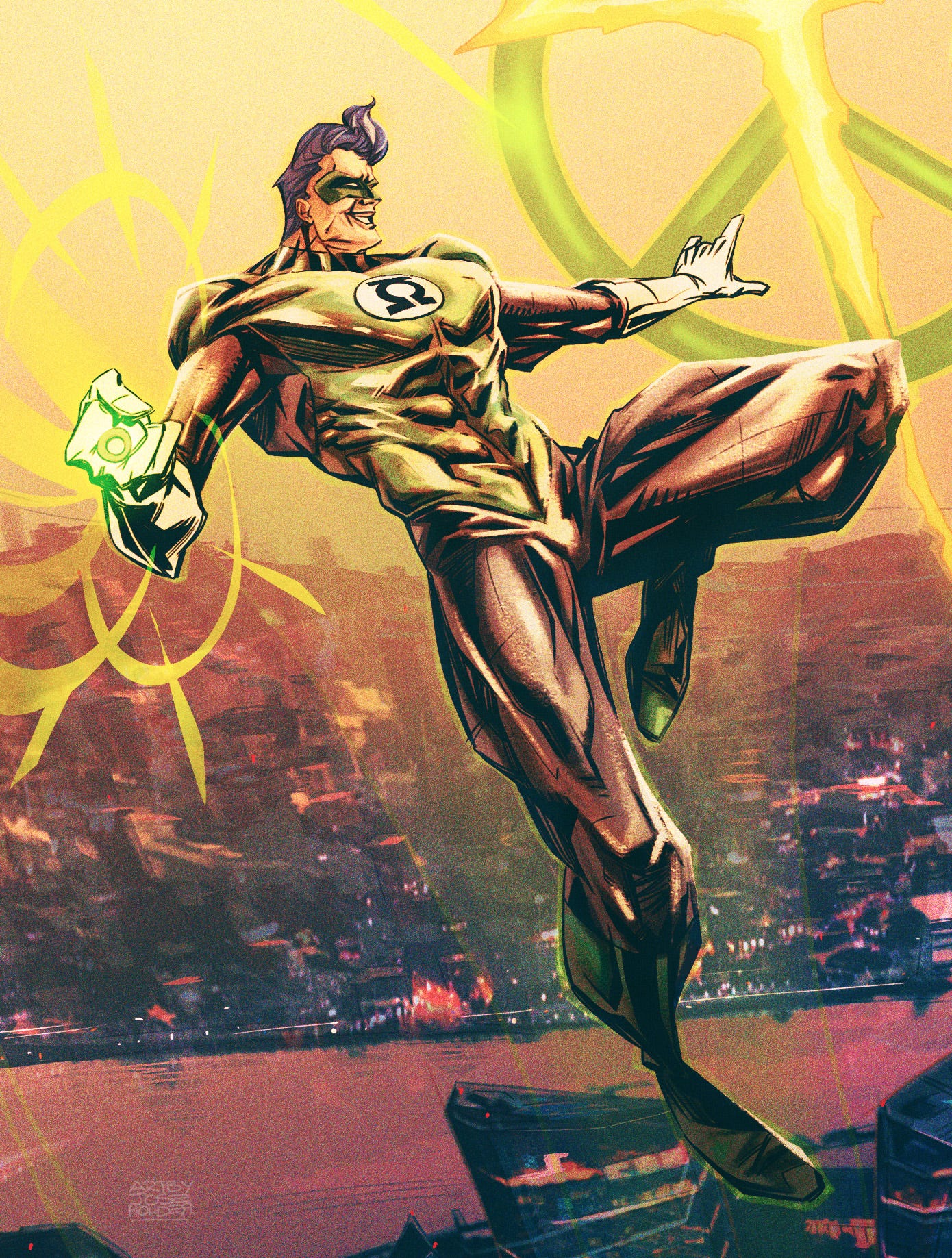

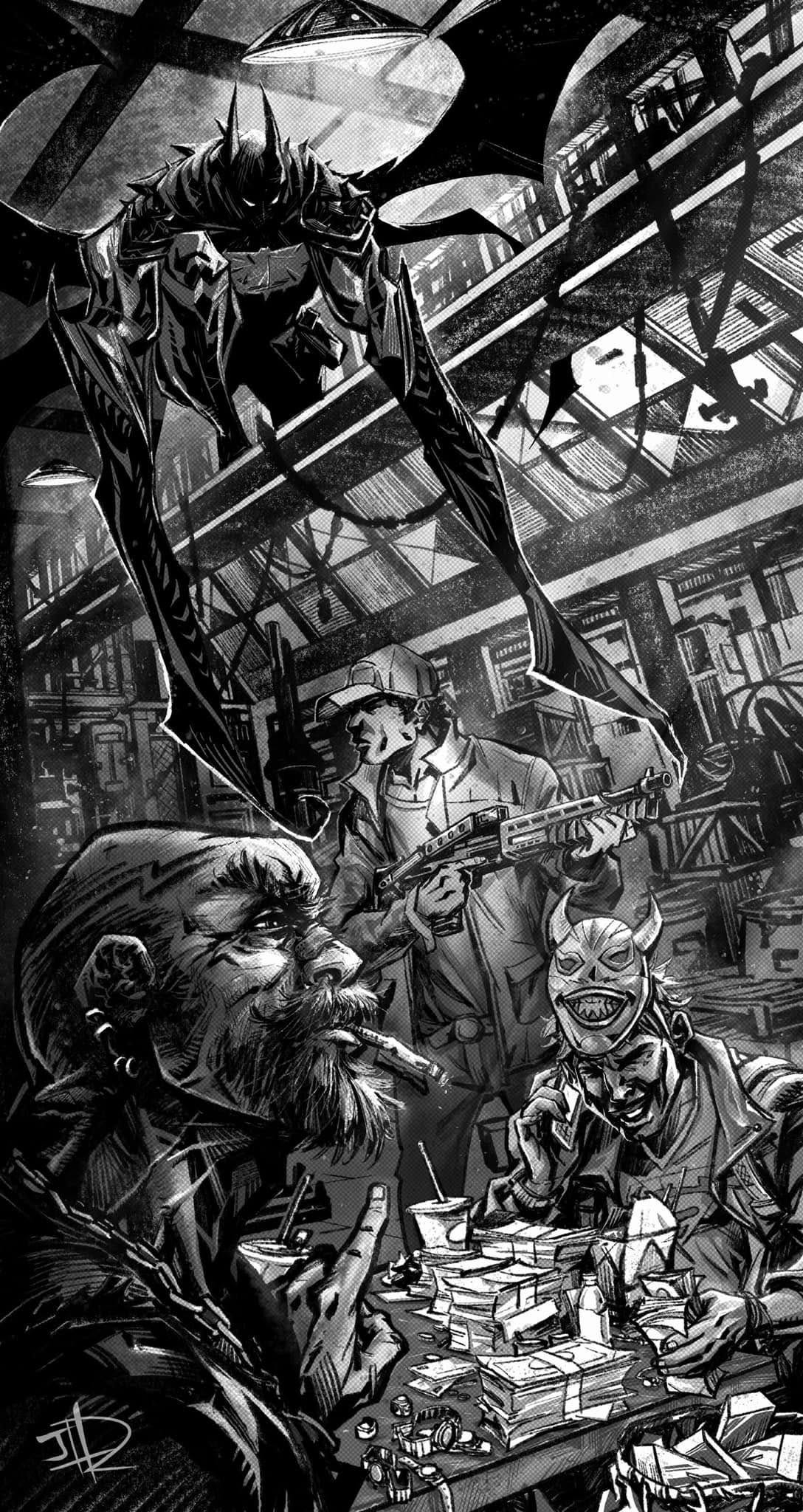

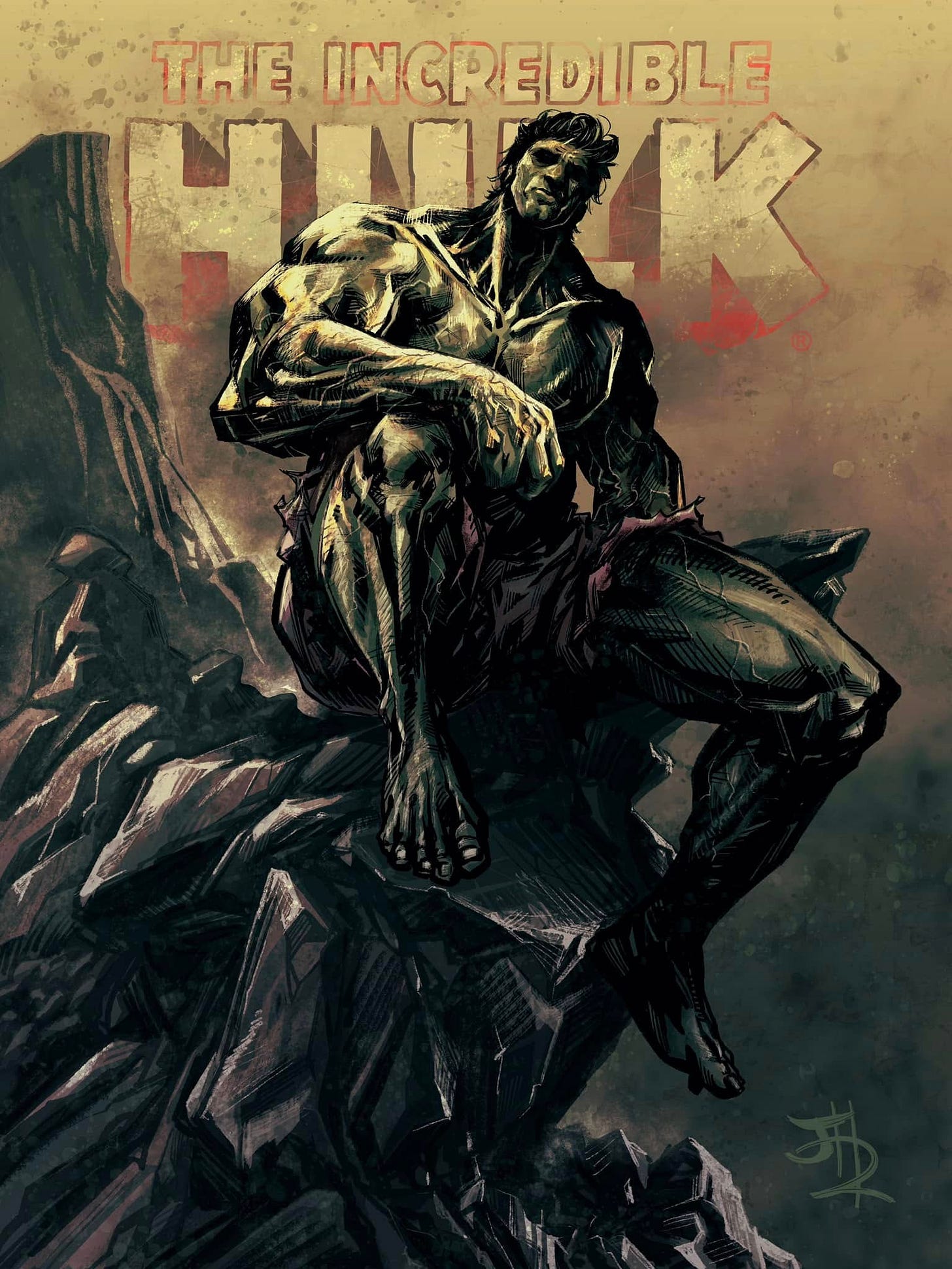

HOLDER: First off, thanks for having me on. I’m just your friendly neighborhood concept artist currently working in video games under the Warner Bros Discovery banner. I’ve played in the arts and entertainment sandbox for three decades thus far, carving a path through advertising, comics, film, tv commercials, architecture, stage, entrepreneurship and even film directing. It’s been a wild ride for sure. I’m self-taught, intensely driven and overly optimistic. Operating as a freelancer in those early years demanded a healthy, forward-thinking mindset, and I guess that never left me.

I was always obsessed with stories and storytelling, as far back as I can remember. From playtime with figurines as a kid, getting lost in comics and novels as a teen, to realizing my affinity for short form writing as an adult––the need to expand my imagination into new mediums has always cast me in the role of storyteller. I only embraced this actuality later on in my career, accepting the plurality of my skills in a world that often dictates we hold our lanes.

BTP: This is exactly what has kept my life and career interesting. Being a multi-hyphenate also helps in staying employed. I watched your film from 2016, titled REDRUBY. I don’t think there was a moment in the production that there wasn’t something interesting going on in the visuals or the sound design. Can you speak more to the specifics of production, timelines, and challenges of bring this film to a reality? Were you able to follow this up with the graphic novel of the same name?

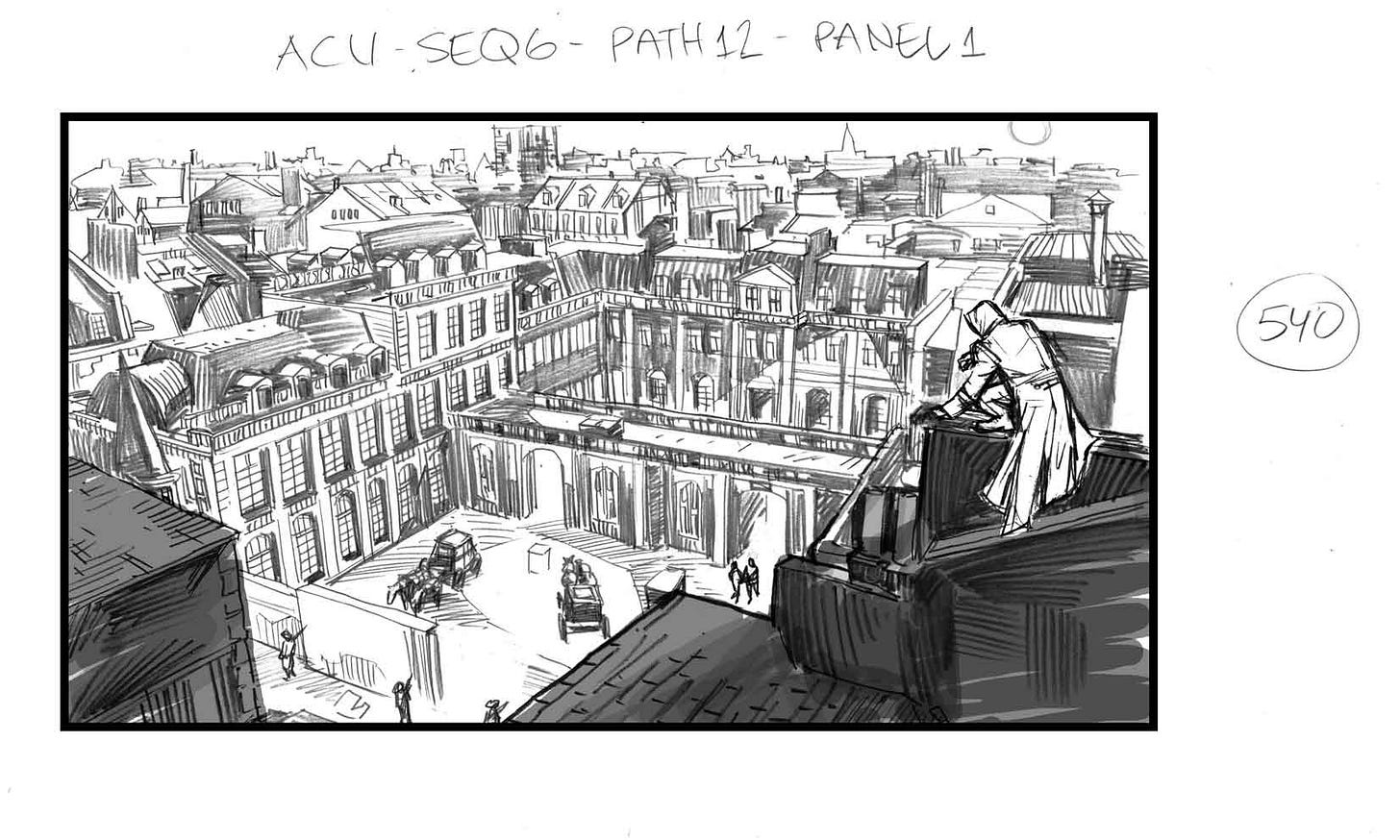

HOLDER: REDRUBY was a labor of love that married all of my interests into one transmedia project. Originally, the film was meant as a bookend to a graphic novel I had in the works. When the opportunity popped up to barter my services as a storyboard artist in exchange for camera equipment, the film’s pre-pro stage took precedence as I fleshed out the script, designed the look, and assembled my 35+ person crew of upstarts. With a little industry experience I put out the call to friends in production and VFX houses, and thankfully they helped me fill those important empty job spots.

I accepted the challenge with total glee and built my own roadmap to production. Locations, set design, production design, boarding, costume design, and producing were just some of the hats I had to wear. Par for the course for 1st time directors. My crew consisted of top-notch talent, starting with the line producer and director of photography, the camera team, accomplished lead and supporting actors, lighting, grips, make-up, wardrobe, sound engineer, sound editor, composer, film editor, special effects, transport, stunts, catering, and on. We shot 4 weekends over 2 months back in 2013. Their passion and tireless work elicited 31 film festival awards worldwide, and became a fan fave at comic cons in the U.S. We premiered at Cinequest in Silicon Valley, and even played at the TCL Theatre in L.A., courtesy of the Holly Shorts Film Festival. I managed to nab the Directorial Discover Award at the Rhode Island International Film Festival!

Challenges? Anyone who has done this knows. It’s a virtual impossibility from the jump. Insurance, contracts, equipment, unions, money, scheduling… Locations that disappear, revoked permissions, malfunctioning equipment, actors that drop, impossible logistics, improbable stunts, disagreements, weather, injuries, budgets that balloon and DIY adventures in guerrilla shooting. Whatever it takes. Failure is not an option. Filmmakers love the challenge of problem solving on the fly. It’s intoxicating, even with the odds stacked against you. But make no mistake about it, every production is a miracle in the making. Filmmakers are generally the bravest, most insane, fanatically positive, sheer will-driven, magicians I know.

BTP: I couldn’t agree more. I’ve experienced similar Highs and Lows on several film shoots. But I always go back for more. Who was your first advocate or earliest mentor that helped in your pursuits?

HOLDER: Growing up in an internet-less age meant cultivating relationships and mentors in the real world, often outside of your immediate circle of friends and family. The artists I looked up to were to be found in the pages of comic books, periodicals of the time, and on the comic convention circuit. Though the latter was the more expensive avenue of the three, I quickly discovered a kinship with like-minded artists plying their trade at various levels of the industry. I appreciated their candidness and generosity, which gave me insights on career expectations, core work ethics and the tools I would need to succeed in the arts. Those early years were informative as they were brutal. The individuals who fostered those personal and professional mentorships would be too numerous to name. A point I always pass on to students of the craft. Find your community.

BTP: How did growing up in Canada affect your approach to building community? Are you still living and working out of Canada or have you moved closer to the film community elsewhere?

HOLDER: Montreal, Canada, always had a thriving film community and affection for movie consumption. The studio landscape is broad and foreign productions benefit from the friendly tax incentives and centralization of numerous VFX houses. It helps that the underground culture of indie creators is so robust, though we often fight for limited funding opportunities and crew onboarding. As a storyboard artist, there were very few dry spells.

BTP: That’s great to hear. I grew up about 70 miles south of Montreal and did not realize what I was missing. Except the cold weather. You guys do cold like nobody else. When you originally set out to study and learn, when did your learning take place and what resources did you have available to you?

HOLDER: Like most illustrators, I recreated what I could get my hands on. Comics, primarily. A local shop opened up in my neighborhood run by a military veteran who loved the medium. As a kid I would sit in the corner of that tiny store for hours, reading, taking in the awe. Posters, pin-ups, limited edition prints… The 70s seemed like the golden era of pop culture iconography, with tv, books, music and film delivering arguably the most memorable offerings of any decade. The resources were everywhere. For aspiring pencilers, WIZARD Magazine and pulp fiction periodicals like The Comic Journal, Alter Ego and Comic Book Artist were fertile ground, stocked full of tips, exposes, and plenty of process art to whet the appetite.

BTP: Oh, nice. I think I got all my information through the COMIC BUYERS GUIDE and COMICS COLLECTOR magazine in the 80s. Did you have any friends who were artists or teachers who were encouraging in school? What was your outlet to share your work and get critical feedback early on?

HOLDER: Montrealers were fortunate to have a short list of talented illustrators working in American comics, some inspired by the Euro style bande desinee, but mostly we boasted a French Canadian and anglophone consortium of creators that spread across indie comics, fanzines, animation, graffiti and fine art. Conventions, drink & draws, exhibitions and periods that spawned the rare bullpen/studio helped to solidify the community. As a workaholic, I missed out on much of those opportunities. Re-connects were a rare and welcomed pleasure to catch up, or rant, if you needed it.

BTP: I’ve actually been doing some stuff with the RAID studios group. So, I know those places exist. Just none here in Seattle. When compared to your early work experience do you feel like you were well-educated to step into a role or was there a larger divide between school and actual pipeline production?

HOLDER: It was the usual chaotic minefield of trial and error in those days. If you were lucky enough reach a convention (that were mostly U.S. based back then, I’m a Canuck), preparing a physical portfolio for review could take you anywhere from weeks to months, and after making the trek down south to wait in a line and meet your fave artist or editor—there were no guarantees that first starstruck critique would yield anything more than, ‘These areas need work. Keep at it. See you in 6 months.’ That was the norm. Some won the contract lottery, most did not. I won shorter gigs with indie publishers, and continued to push into film and eventually, video games.

The market and its community of artists were the true curators of skill and expertise. They single-handedly nurtured and championed new voices to the field, exacting wisdom, and if you were lucky, a golden referral. There was no preparation for the comic book medium except in its execution. The sticky part for most artists lay in service of the client, where the uninitiated stumbled out of the gate, victims of underdeveloped soft skills. Communication, problem solving, interpersonal, critical thinking, etc. Illustration is a solitary sport, and it took a minute to get my bearings as both an artist and a salesman.

BTP: Interesting, I don’t think most people consider the salesman aspect. Usually, it’s about the work speaking for itself. But communicating that one is competent and dependable only bolsters your efforts. When you were first putting submissions together, were you writing out scenarios to draw or would you work with a writer? What was your first comic gig and how did it go for you?

HOLDER: Artists always struggle with the quantification and monetization of their works. Especially in the beginning. I made sure to do my research, ask around, and read articles and magazines that modelled the culture. Many early jobs were pro bono, low paid, or bartered. I relished knowledge and experience over remuneration, embraced value over speed, and built strong relationships that benefitted my career.

My earliest portfolio contributions were based off pre-existing written content, be they comics, books, or tv and film scripts I bought at shows. Paid art projects were fun, sometimes silly, and often sexually explicit. Basically, high quality low brow stuff on the indie circuit, but it sharpened your teeth, put your name into the mouths of convention-goers, and opened up doors to new print jobs. Some paid for the work, some didn’t, but making my mark was the goal back then.

BTP: You’re gonna make me dig into back issues, aren’t you? 😄 What do you feel was missing in your education vs. the reality of the job? How would you fix this?

HOLDER: The creators. That’s where the education was and still is, through the divergent experiences and perspectives on path and process. The reality of illustration, once built on a strong understanding of the fundamentals, boiled down to relationships, readability/execution, market trends, and a shitload of luck. Being unafraid to ask questions and take constructive criticism of your work, push through those qualitative boundaries with humility and respect––all of it factored into your professionalism. The digital realm has dissolved many of those formal barriers to entry, but that only reinforces the notion that you still only get one shot to make a great impression. Do your homework on the reviewer and their/employer’s body of work, and have commensurate samples in hand/online, coupled with the proper patience/attitude. You’ll be remembered for that. Trust me.

Most storyboarding gigs retain the same fundamentals, and it’s just the medium that we boarders need to adjust for. Eventually, digital illustration expedited my turnover time, eliminating large scale edits, scanning, and ensured more product variation. Animatics demanded updating my skillset to include more digital software, and elevated the craft to simulate short film sequences / pre-vis.

Directing, while demanding, played very well into my natural strengths as a storyteller and work ethic. When you’ve planned well artistically and keep an open mind to new ideas and organic problem solving, the mechanics of film can really be delegated to people who know their role and responsibilities far better than you.

If you find yourself feeling overwhelmed in a new role, rely on your network of peers to keep you accountable. Attack your problems in smaller, manageable segments, if possible, slowly building the confidence and momentum to cross the finish line. Preparation is everything, so do your homework, but don’t underestimate the importance of breaks and downtime. These are necessary to restock your creative juices and bolster healthy habits. Your relationships need them to!

BTP: There’s a lot to unpack here. Fundamentals seem to be at the core of any artists ability to shift and migrate from one industry to the next no matter what the ask or software that is required. Does it ever feel unsettling or unfocused that there are these techniques, say for concept art, that are more heralded because the software creates a look that is becoming trendy or popular? How do you evolve your style and ability to stay in demand, if at all?

HOLDER: Great question! Certainly, book publishing has its ebbs and flows as market trends and consumer appeal spark new visions for editorial depts. But as you know, those demands never really hold sway over the indie storyteller. Commissions for cover art, books and albums were generally at the whim of the contractor, and portfolio diversity reigned supreme in this regard.

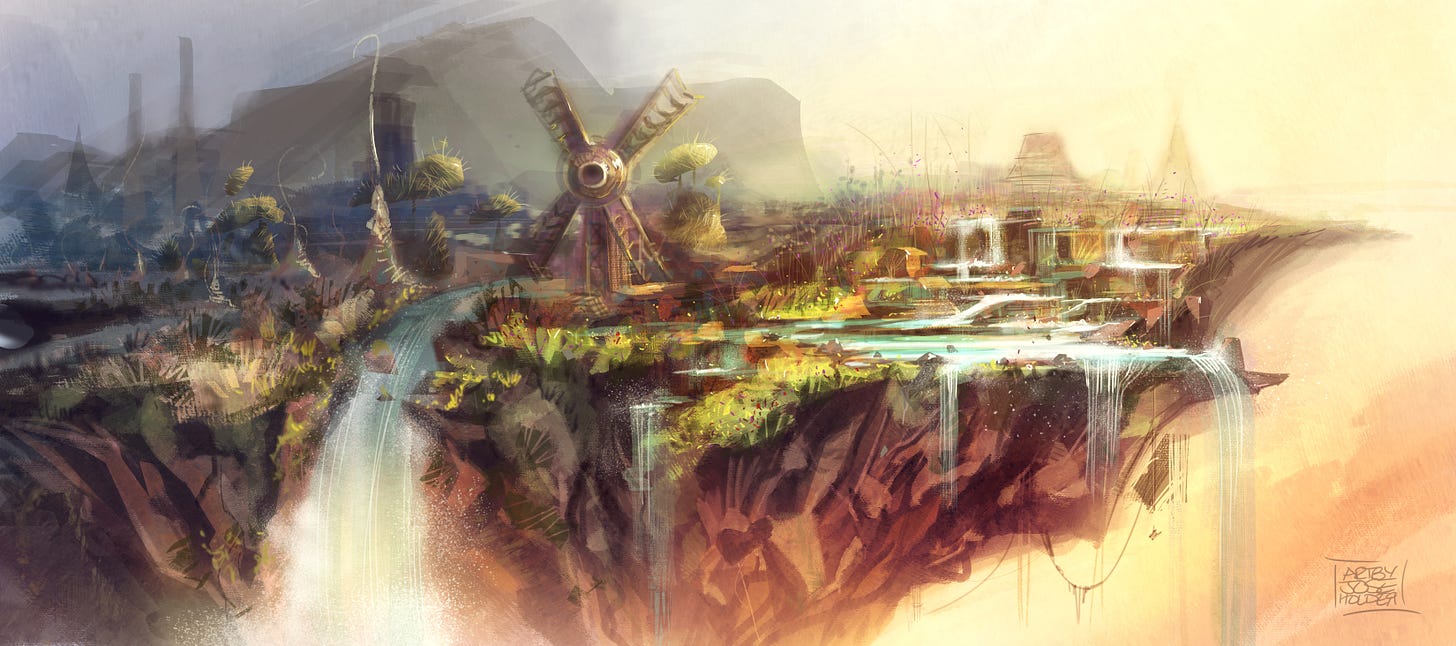

Concept art has always existed as a mixed bag of traditionally trained craftspeople and talented digital warriors, some who managed the transition by blending old world fundamentals with cutting edge tech. Streamlining workflows with Photoshop wizardry, photography, painting, life drawing, and industrial design skills. Photo-bashing, overpaints, digital brush packs and 3D modelling changed the expectations of art management teams and ushered in a new age for concepts. The work is more finely curated now, iterative, polished to perfection, and can be devoid of many of the imperfections that once celebrated individual style and expression. And maybe that’s okay, a natural evolution of technology and all. The end result is the ultimate goal. The shiny, entertaining, laboriously manicured gem we bring to the masses. We can celebrate the work through its achievement, and through each other.

BTP: I have my own issues with the “overly polished” concept work out there. It’s a great portfolio builder but locks everyone into realizing this one image with little wiggle-room to throw in your own special sauce. But hey, people want guarantees, I guess. As creatives we tend to have personal goals or aspirations for ourselves. What are yours and what does achieving them look like in the next 5 to 10 years?

HOLDER: More writing, more directing, and a fiercer concentration on my own comic-based projects. Expect a host of books in my stable of transmedia possibilities. I’ve spent the last few years studying in the producers’ circle of television and film, so partially flexing those muscles for indie projects and my own bespoke IPs would be amazing. Directing with Unreal Engine for game cinematics, television or film would certainly amalgamate many of my skillsets and unlock new avenues of storytelling. That’s exciting.

BTP: I really dig the power of the Unreal engine, especially in Virtual Film productions. Do you see yourself as a one-man studio or would you grow something bigger to execute larger projects?

HOLDER: For now, it’s all about learning how to bridge both worlds visually, the conceptual aspect and digitally fluid environments. Videogames is a natural testing ground to prove out new modes of storytelling and push boundaries that marry both live action and 3D in seamless ways. I’m looking forward to exploring the infinite possibilities for filmmakers to move beyond real world locations and onto sets rooted in imagination.

BTP: You seem ripe to take on the role of Cinematic Director! I found it was a great blend of filmmaking and storyboard work. All things being equal, what are your biggest fears in your career currently and what are you doing to keep those in check?

HOLDER: No fears, really. I naturally have to remain competitive in my industry by being cognizant of new ways to streamline my craft. I’m generally curious and patient, so the urgency of change never truly eclipses my focus. Every project and team require different creative outlooks, processes and execution. Adaptation is key, and creating a niche for yourself does ensure some measure of longevity.

AI isn’t coming, it’s here. But I’m not apprehensive about the potential fallouts of this new paradigm. Change is painful, destructive. There’s no doubt this will equate to an ELE level disturbance for many of us artists as industries find new ways to augment their pipelines, but I firmly believe we should exploit the science to inform our own language models and artwork. This should allow us to iterate faster and perform automations that traditionally shackled us to rigid timelines and fewer creative fields of interest. Imagine ten versions of you tackling various concepts of future promise?

BTP: Whatever optimism juice you’re on; I’d like to buy a case! 😄 Damn, that is a great outlook. Not to rain on your parade, but I’m curious your thoughts about so many game studios closing down, some with even very successful titles, over the past two and half years. Do you think there’s room in the creative fields for all that free-floating talent or are you looking over your shoulder more?

HOLDER: It’s definitely a turbulent period for the gaming industry. Studios need to be very reflexive to players, their preferences and gaming habits. Trends are always changing, and we have to continue to be innovative in the face of market volatility and consumer demand. Artist teams are composed of all manner of specialists, generalists, and blends of seasoned vets and junior upstarts with decades of experience between them. These people, as most entertainment sectors go, develop lasting relationships while entrenched in production. When one studio closes, you’ll often find waves of sympathetic peers eager to post the latest job openings or to champion those they’ve served alongside. It’s a tight knit community. We look out for one another and are quick to celebrate our comrades' accomplishments, because we love games and the people that make them.

BTP: Difficulty in the trenches I think warrants a certain brotherhood/sisterhood. It’s how we tend to survive. Speaking of better things, describe the perfect day for yourself. Comparatively, what would be the perfect workday?

HOLDER: The perfect cup of java over some good reads, a workout or cold plunge, writing (novel, script), late breakfast, more writing or illustration work, dinner and a good film with family (at home), and a return to some uninterrupted late night creative pursuit.

That IS the perfect workday.

Comradery is the magic sauce that makes those work experiences (and tougher days) endurable. It doesn’t matter whether we’re in person or online, in the same room or scattered across a soundstage. The jobs blur, but those peer relationships, our joint pursuits, emotional triumphs, singular achievements, and Hail Mary’s in the 11th hour––those milestones last forever. More than anything, I doggedly covet good working partners and positive team dynamics. Lifeblood.

BTP: Truly. Sounds like an aspirational recipe we could all use. When you’re not working creatively what other outside pursuits do you have that feed your soul?

HOLDER: Comic book pin-ups and sketches help fuel the soul. Writing sharpens my mind; novels keep me inspired. Flying lessons challenge me structurally. My blood flows at 24fps, so prepping my next short film is always on the horizon. Calista Way is an award-winning script I wrote during the pandemic that I’m hoping to shoot soon. Of course, lots of classes, online tutorials and study to level up at work.

BTP: There we go. Getting after it. I like that, Jose. What advice would you give to your younger self regarding your life’s path thus far?

HOLDER: Surrender sooner. The path isn’t a straight line. Life is meant to be fluid, chaotic, unpredictable, transformative. Find meaning in the madness, purpose in the process. Erase the obsessive need to control, predict, feed expectations, or target goals. That’s the hat trick. Less is more. And even though this was realized in my early adulthood, I would so ‘John Conner’ the notion, travel back even further in time, and seed it in my youth. All that, and pay more attention to the double slit experiment;)

BTP: Heh. You basically named all the things we struggle with, sometimes into our adulthood. Growing up near the New York/Ontario border where we at least are 50% Canadian I’m familiar with the term “hat trick”. How much into hockey are you or any other definitive Canadian pursuits?

HOLDER: I haven’t played hockey since I was a teen, and street hockey even before that. Football, basketball, soccer, and volleyball eclipsed my time in secondary school. All these years later, I’ve swapped those golden pursuits for a Cintiq Pro and a Gold’s Gym membership. As a Canuck, I do shovel copious amounts of snow living in the countryside and enjoy the occasional poutine once a year!

BTP: I do not miss the snow! Not even a little. What is the most difficult thing you’ve had to do in your career and how did you make it through?

HOLDER: This is an easy one. It would be the nexus where art and business meet, and the effort and appreciation needed to navigate both worlds with equal scrutiny and empathy. Many times, both paths skewed disparately, favoring my creative mind (naturally). It took lots of hard work and dedication to marry the two worlds in a way that kept me inspired and excited to push boundaries.

The other silent threat involved the unspoken mindset by industry stakeholders to pigeonhole creators with unbridled potential. The only way to break down those barriers is to DO the deed. The act builds up momentum, scar tissue, obliviates procrastination, guarantees humility by failure, and delivers massive returns in the form of delayed gratification and self-worth. Onlookers will be forced to re-evaluate your value, and that’s a great position to be in.

BTP: Can you be more specific, like what did that look like and who were the players involved in this scenario?

HOLDER: Kinda comical looking back. You’ll relate. Many times, artists have to reprove themselves as they navigate the arts. You’re only as good or relevant as your last gig (they say), and even with burgeoning portfolios, clients sometimes look for clones of past encounters. Illustrators still jump through hoops to be accepted, even when the content is fundamentally created the same way. This was the case for me. As a comic book artist I can create concepts, characters, environments, storyboards, animatics, etc. Storyboarding is also mirrored across mediums like tv commercials, shows, films, animation, video games… it’s all relevant and interchangeable. But while bleeding borders can be tough, this is where being a good salesperson opens doors. I still had to communicate my ability and passion to pursue the medium of choice. Challenges are necessary for growth. You can’t be afraid to reinvent yourself. Resilience is key, and longevity, at least in the arts, often demands we strive for adaptability.

BTP: Yeah, that’s a problem. People tend to only see what’s in front of them. It’s a lack of either imagination or information on their part. But if you want something bad enough, you’ll prove your worth.

BTP: We really appreciate your thoughtful answers and taking the time to join us, Jose. Please let our audience know where they can find out more about you and your work.

HOLDER: Many thanks for the opportunity to play in the BTP sandbox and engage with your fans. I had a great time!

Website: https://bio.site/JoseHolder

Portfolio: https://www.joseholder.com/